The Trifecta of Competitive Toolmaking

Process, technology and people form the foundations of the business philosophy in place at Eifel Mold & Engineering.

#fiveaxis #casestudy

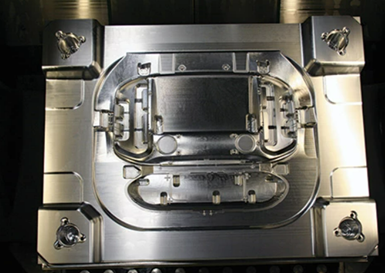

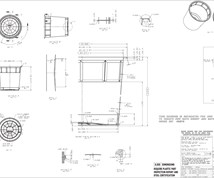

Here is a typical example of the sort of work Eifel Mold & Engineering sees day-in and day-out. Tooling for steering wheels and airbag systems are a particular specialty for the shop.

Even the most sophisticated technology can’t accomplish much if it’s not run by people who understand not only how to operate it, but how best to apply it. That’s the basic premise driving virtually all activities at injection mold manufacturer Eifel Mold & Engineering. When it comes to technology, process, and people, “you have to invest in all three to be successful,” says Richard Hecker, owner and CEO.

This philosophy hasn’t always been clearly articulated, let alone codified as an all-but-official tagline for the Fraser, Michigan-based injection mold manufacturer. Nonetheless, Hecker says the essence of the three-pronged approach has been in place ever since his father, Josef Hecker, founded the shop in 1973. Through the years, it has influenced the shop’s investments in capabilities ranging from manufacturing feasibility studies to in-house sampling. Yet, the philosophy is perhaps best evidenced in the process that forms the foundation of this expanded service offering: the production of quality tooling, mostly for automotive interior components.

Featured Content

The Process

From design all the way through assembly, conducted in the area shown here, Eifel’s process is virtually paperless. That’s thanks largely to a home-grown ERP system and a strategy of incorporating all information people need to do their jobs into color-coded CAD designs. Thanks zero-stock machining, the shop uses the spotting press visible on the right far less frequently these days.

One major turning point for Eifel was a move into zero-stock machining, which improves throughput by eliminating the need for downstream processing. In fact, the shop has committed so fully to this process that much of the time, its spotting press just takes up space, Hecker says. Making this work requires what he calls a “systems” approach, and there can be no weak links.

Most decisions aren’t left to individual machinists, but to the design department, which carefully engineers every fit and clearance. Given all the work at the front end of the build, an in-house-developed ERP system has proven critical to keeping the shop on schedule. Another contributor to synergy throughout the process is the use of color-coded CAD designs, which communicate specific job instructions to operators via shopfloor kiosks. (For example, different colors might indicate whether a hole needs to be tapped or just drilled.) In fact, operators in this paperless environment haven’t seen a setup sheet in two years, Hecker says.

The Technology

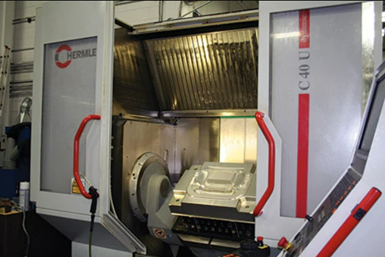

Given the preponderance of undercuts and other tough geometry in its work, Eifel relies heavily on five-axis machining centers like this C 40 U from Hermle. Most recently, the shop added a DMU 50V from DMG MORI.

Given the frequency of undercuts and other tough geometry, the shop’s zero-stock machining strategy relies heavily on five-axis equipment. Better access to part features through additional axes of motion not only reduces setups, but enables moving the spindle closer to the work. As a result, the shop can use shorter, more rigid tool assemblies that provide greater precision and smoother surface finishes.

The People

Getting used to the additional axes of motion proved far easier than expected, Hecker says. After all, many applications require only 3+2 machining, a process that isn’t far removed from programming a three-axis VMC, he says. Nonetheless, he emphasizes that the transition could have been far more painful without the right people.

Committing to new ways of doing things, he explains, can’t just come from the top. Shopfloor-level employees also had to buy in, both to the process of zero-stock machining and to the five-axis equipment that facilitates it. This requires people with confidence in their abilities, people who trust one another, people who are open-minded enough to understand that taking ownership of advanced techniques and equipment is critical to the future of the shop and their own careers.

“Within a good business model, each of these three areas should be just as important as the other,” Hecker concludes. “We put the best people in place and support their growth while devoting resources to obtaining the right equipment and implementing the best methods.”

RELATED CONTENT

-

True Five-Axis Machine Yields More Throughput, Greater Productivity

CDM Tool & Mfg. Co. LLC increased shop capacity thanks to a versatile high-speed/high-accuracy five-axis Fooke mill capable of cutting very large workpieces quickly and accurately with fewer setups.

-

Five-Axis Graphite Mill With Automation Debottlenecks Electrode Machining

Five-axis electrode cutting enabled Preferred Tool to EDM complex internal screw geometry on an insert that otherwise would have had to be outsourced.

-

Improve Mold Machining With Equidistant Offset, Rest Finishing and Innovative Five-Axis Toolpath Strategies

The right CAD/CAM software helps mold builders better manage complex tool paths, improve the effectiveness of CNC finishing tool paths and take advantage of innovative five-axis machining toolpath strategies.

.jpg;maxWidth=970;quality=90)