How to Make an Informed Hot Runner Decision

Appears in Print as: 'How to Make an Informed Hot Runner Decision'

A proper hot runner assessment requires evaluating and calculating key runner system variables.

#basics #FAQ #automotive

Evaluating the cost justification for a hot runner mold requires careful consideration of cycle time, material type, annual volume, available press size and power consumption, as well as the cost of utilities, resin pricing, allowable regrind percentage and labor rates. Here are three key areas to consider:

1. Cold Vs. Hot Process Considerations

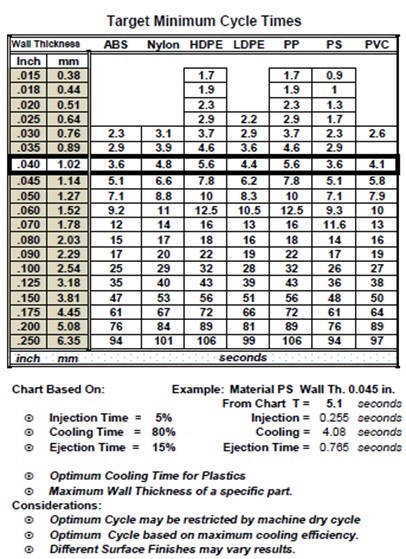

Cycle time is the primary cost measure of the molding process, and cooling represents about 80% of the molding cycle (see Figure 1). The thicker the part, the longer the cycle time. However, the runner could determine the cooling time, and increase cycle time more than expected if the runner is thicker than the part.

Featured Content

Figure 1

Images courtesy of Richard Hagfors.

The minute the resin leaves the machine barrel, the material starts to cool and solidify. This, in turn, causes injection pressures to climb and can yield unfilled parts, stress and warp. Limit the l/t ratio (length of flow versus part thickness) to avoid this outcome. Generally, a ratio under 100 is considered general-purpose molding and does not require increased injection pressures.

In a cold runner mold, the l/t ratio is measured from the start of the cold sprue, where the material leaves the heat source and begins to cool, which continues through the entire runner to the furthest point in the part (last point of fill). For example, 1 mm (0.039 inch) thick resin can flow easily 100 mm (3.94 inch). However, if a hot runner is used, the l/t ratio starts at the gate, reducing flow length and the injection pressure required to fill the part.

The higher the ratio, the more injection pressure is required to fill the part. A cold runner is included in the l/t calculation when the molder measures at the point of no added heat. This is one reason hot runners are appealing and can make the difference between molding a good or bad part.

Cold runners can also affect fill time, recovery, and residence time in the machine barrel and hot runner manifold. Every cycle involves the processing of the cold runner, as well as the parts.

Most molders adapt the mold and process to their current machines to optimize performance instead of using mold requirements to size the barrel. Injection molding machines equipped with reciprocating screws have a best-case range, so the process engineer must find the balance among residence time, temperature and pressure to deliver continuous melt to the mold.

Hot runner systems have some limitations. For example, manifold melt channels are typically manufactured in fixed melt channel diameters to limit pressure drop and maintain a consistent flow. The material in the manifold is considered part of the residence time, so always consult the material supplier on recommended temperatures and residence times. Also, melt channel size and complexity can impact color change.

Evaluating the cost justification for a hot runner mold requires careful consideration of cycle time, material type, annual volume, available press size and power consumption, as well as the cost of utilities, resin pricing, allowable regrind percentage and labor rates.

2. Material Considerations

Most polyolefin resins can be reused without issue. Engineered materials can be limited in regrind content because each time the resin is processed, it experiences another heat history that can degrade melt quality and impact performance, color, rigidity, tensile strength, etc.

Keep in mind, not every runner makes it to the granulator, and not every pellet makes it back to the hopper. While eliminating the cold runner can reduce scrap, a complete hot runner system might not be cost-justified based on low annual volume. The cost of an entire hot runner system may take longer than a year for payback. It might be wise to consider a hot/cold combination or at least a heated sprue bushing. The sprue is typically the thicker portion of the runner, and eliminating that and/or a portion of the runner could have an impact on the cycle time, resin consumption, scrap, etc.

In some applications, a hot runner system might eliminate scrap from unusable runners, but based on the required shot size volume (total volume of parts and runners) relative to the barrel volume, and it might reduce the consumption causing the barrel of the molding machine to be too large. Residence time on engineered materials would increase, which may cause other issues. For example, too small a shot can be challenging to process even with olefins.

3. Energy Considerations

Hot runner systems run on electricity like granulators. An injection molding machine takes roughly 1 kiloWatt (kW) to process 1 kg (454 lbs) of resin. Reducing the shot size to parts only can have a significant impact on power consumption. It stands to reason that only heating, melting and processing parts takes less energy than parts and runners.

When deciding between a cold or hot runner system, consider all of these variables, which combined can increase productivity and energy savings, improve material utilization and reduce floor space and noise requirements on the shop floor.

RHH Advisor and Consulting—Injection Molding

646-352-3021

rick.hagfors@gmail.com

Rick Hagfors is a consultant and advisor to the injection molding industry with over 40 years of experience in molding machines, injection molds, hot runner systems and process control.

RELATED CONTENT

-

Texturing Molds for Thermoplastics: Factors for Success

Factors to consider when selecting a texture or grain for a thermoplastic mold or die.

-

Hot Runners and Valve Gate Systems: A Moldmaking Team

Valve gates provide several advantages when using hot runners, including better appearance, safety and an overall better product. There are several types of valve gates, and it is important to choose the right one for your project.

-

A Different Approach to Mold Venting

Alternative venting valves can help overcome standard mold venting limitations and improve mold performance.